Press Release

Household Financial Resilience Index Afhri Q2 2024

16 January, 2025

The Altron FinTech Household Resilience Index (AFHRI) for the 2nd quarter of 2024 confirms negative impact of high interest rates on household finances

Background to the AFHRI

In recognising the need for data that provides more clarity on the financial disposition of households in general, and their ability to cope with debt in particular, Altron FinTech commissioned economist and economic advisor to the Optimum Investment Group, Dr Roelof Botha, to assist in designing this index. The index comprises 20 different indicators, all of which are directly or indirectly related to sources of income or asset values. The AFHRI is weighted according to the demand side of the short-term lending industry and calculated every quarter, with the first quarter of 2014 being the base period, equalling an index value of 100. All the indicators are expressed in real terms, i.e., after adjustment for inflation.

Media Release

Johannesburg, 16 October 2024 – The results of the most recent Altron FinTech Household Resilience Index (AFHRI) were released today, confirming the continued financial pressure on South African households, mainly due to the high interest rates over the past two years, which have raised the average debt cost burden to its highest level in 15 years.

According to economist Dr Roelof Botha, who compiles the index on behalf of Altron FinTech, the restrictive monetary policy stance by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has come at a huge cost to the economy. Botha says: “One of the most worrying trends in the latest AFHRI is the year-on-year decline of 3.3% in the ratio of household income to debt costs. Merely two years ago, in the first quarter of 2022, households were sacrificing 6.7% of their disposable incomes to pay for debt costs. This ratio has since increased by 36%, with households now having to spend 9.1% of their disposable incomes on servicing debt.”

Botha adds that: “The decision by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank at the end of 2021 to follow a restrictive monetary policy stance has resulted in a relentless increase in the official repo rate, which automatically feeds into the prime overdraft lending rate of the banks.” Botha further notes: “South Africa’s prime rate was 7% at the end of 2021, but jumped to 11.75% in May 2023, where it stayed for 16 consecutive months, representing an unheard-of increase in the cost of credit (and capital) of 68% - based on the real prime overdraft rate. The unwarranted increases in lending rates have a stifling effect on demand in the economy, especially household consumption expenditure and new investment in productive capacity by the private sector. “

The flaws of restrictive monetary policy

According to Botha, at least three fundamental flaws can be identified in the overly restrictive monetary policy approach of the MPC over the past two years. The first being inconsistency. During the tenure of the previous Governor of the Reserve Bank, Gill Marcus, the average real prime rate was just above 3% and real GDP growth averaged 2.5% over a five-year period. Within one year of her retirement, the new MPC raised the real prime rate by 57% to a level of 4.9% and four years later, the real prime rate stood at 6% - an increase in the cost of capital and credit of 94%. It remains a mystery why the MPC decided to lift the prime overdraft rate to a level of 11.75% in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, when it was 10% just prior to the Covid pandemic and also considered too high then by the standards set by the MPC under Gill Marcus.

The second flaw is a lack of understanding over the causes of higher inflation immediately after the worst of the lockdowns imposed by the outbreak of the Covid pandemic. The spike in the consumer price index was mainly the result of three supply-side shocks, namely the increase of 720% in global shipping freight charges (between the third quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2021); the 430% increase in the price of Brent crude oil (between April 2020 and the beginning of 2022); and lower levels of capacity utilisation in South Africa’s manufacturing sector, which increased fixed overhead costs per unit of production. “Excess demand had nothing to do with the temporary rise in the CPI””, says Botha. “By raising interest rates to record high levels, the MPC’s policy approach only served to reduce aggregate demand and restrict the ability of the economy to recover from the effects of the Covid pandemic”.

The third flaw is the undue importance given to inflation expectations. Apart from the fact that significant variations permanently occur between the results of quarterly surveys on anticipated future inflation and observed inflation, the samples for these surveys are minute and devoid of meaningful academic substance. Extensive research by Reid (2012 & 2021) has revealed that a relatively large number of respondents either declare that they have no knowledge of the subject or answer with ridiculously large numbers. The crux of the problem with using inflation expectations as a basis for conducting monetary policy has been succinctly stated by Reid (2021) with the following conclusion: “expectations matter, but they are unobservable.”

Counting the cost of record high interest rates

The costs of overly restrictive monetary policy have been huge. In the event of the debt cost servicing ratio having remained at 6.7%, cumulative household disposable incomes would have been R172 billion higher. Due to the effective parity between disposable incomes and consumption expenditure, this would have translated into an equal increase in total demand. Based on the fairly stable relationship between aggregate demand and taxation revenues, National Treasury would have pocketed an additional R42.9 billion – enough money to build 370,000 low-cost houses and create 244, 000 jobs in the construction sector supply chain.

The debilitating effects on the economy of record high interest rates are also visible in virtually every economic indicator of note, including negative per capita GDP growth and lethargic trends in indices such as the Afrimat Construction Index and the Drive.co.za Motor Index. South Africa’s residential property market has been exceptionally hard hit by the high interest rates, which have served as a disincentive for home buying. Since the higher interest rates started to bite, the BetterBond Index of home loan applications is down by 31%.

Furthermore, it should be of huge concern to government’s economic policy makers to witness the recent increase in the country’s unemployment rate. Since the fourth quarter of 2018, formal sector employment increased at a paltry rate of 0.1% per annum – considerably lower than the average annual increase in the labour force of 1.8%. Moreover, it is alarming that the number of unemployed persons, including discouraged job-seekers, has increased by 2.6 million over this period – threatening the ability of National Treasury to continue paying the so-called Covid grant, whilst also acting as a potential source of social unrest. “It is high time that the combating of relatively benign inflation is weighed up against the negative effects that high interest rates inflict on job creation and economic growth.” concludes Botha.

Results of the AFHRI for the first quarter of 2024

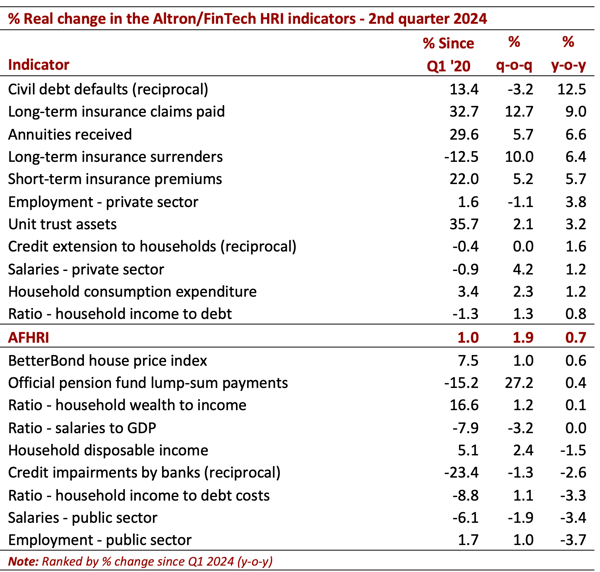

The table below summarises the performance of the different indicators comprising the AFHRI over three different periods, i.e.: since the last comparable quarter before the COVID-19 lockdowns – Q1 2020; quarter-on-quarter; and year-on-year (percentage changes in real terms). The period since the first quarter of 2020 is regarded as relevant to gauge whether the financial resilience of households has fully recovered from the pandemic or not.

The downside

In assessing the latest trends emanating from the constituent indicators of the AFHRI, the problem areas for the indicators that possess a relatively large weighting are salaries in the public sector, employment in the public sector, household disposable incomes and the ratio of household income to debt costs. These indicators are not expected to increase in meaningful terms until such time as interest rates have declined to at most the same level as before the Covid pandemic, i.e. a prime rate of 10% or lower.

On a positive note

Despite the mediocre improvement of the AFHRI in the 2nd quarter, some positive trends exist amongst key constituent indicators, including the following:

- Private sector employment has risen by 459,000 since the 2nd quarter of 2023. With interest rates bound to be lowered further in November and early in 2025, and the government of national unity now engaged in a closer relationship with business leaders in the private sector, the prospects for further employment gains have improved.

- Following a lengthy period of decline, real levels of labour remuneration in the private sector have increased, both on a quarter-on-quarter and year-on-year basis.

- The rise in the value of unit trust assets, which serves as a proxy for potential investment income for many households, is bound to increase further in the second half of the year, mainly as a result of the recent new record for the JSE all share index.

The MD of Altron FinTech, Johan Gellatly, says: “The latest AFHRI report is deeply concerning. Although the GNU has created expectations for growth amongst international and local investors, the persistent issue of unemployment is unacceptable. We urgently need to capitalise on our growth mindset and support every sustainable initiative that attempts to create jobs. There is no quick fix. The indicators are clear, we require all hands-on deck to actively reduce unemployment. South Africans have proved themselves to be remarkably resilient. They have managed to make ends meet, even when their disposable incomes are under dire pressure due to sustained periods of extremely high interest rates.

All indicators, including the AFRHI, point to the need to lower interest rates in order to start assisting consumers. This is equally important in terms of growing the economy, attracting investment and reducing unemployment.

While a significant proportion of Business SA is sitting on the sidelines and playing a ‘wait-and-see’ game to ascertain whether they should invest or not due to the tight monetary policy, at Altron FinTech we are constantly applying our minds with our customers on how best we can use the resources at our disposal to grow our businesses and assist consumers by introducing cost-friendly products and services.”